Information in the broad sense exists as identifiable objects in Popper's world 3, and can be evaluated and qualified against at least two dimensions of cognitive value: quantity (i.e., how many elements of information exist in relationship to a particular question), and epistemic quality. Quantity is easy to grasp as Robertson (1998) demonstrated, because we can often measure and count the information objects we are dealing with. Lyman and Varian (2000, 2002a) added up the total volume of information recorded by humans each year as measured in bytes. (For the record, in the year 2000, "The world's total yearly production of print, film, optical, and magnetic content would require roughly 1.5 billion gigabytes of storage. This is the equivalent of 250 megabytes per person for each man, woman, and child on earth".)

On the other hand, the dimension of epistemic quality is slippery and has not been carefully studied in the kind of framework I present here. In my usage following Popper (1972), information of higher epistemic quality tells us more about what we want or need to know about the world than does information of lower epistemic quality. For example, Lyman and Varian (2000) note, "Printed material of all kinds makes up less than .003 percent of the total storage of information. This doesn't imply that print is insignificant. Quite the contrary: it simply means that the written word is an extremely efficient way to convey information." Some of the best frameworks I have found for representing and explaining concepts of epistemic quality come from the intensely practical area of military affairs.

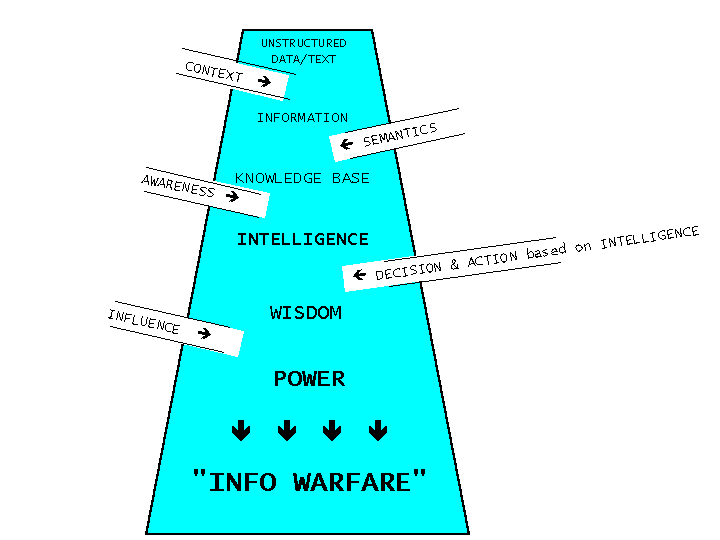

Figure 1. Ian Coombe's Information Definitions and Transformations. Ó1995 by Ian Coombe, reproduced with permission, as published in The Australian Army Information Management Manual, Version 2.

Figure 1 and following discussion are based on concepts expressed by Ian Coombe (1994-1999), in a still incomplete thesis, which I first encountered as a framework Coombe prepared for the Australian Army’s Information Management Manual37. This ranks data, information, knowledge, and possibly intelligence and wisdom along an axis. Sveiby (1994) and others in the organizational knowledge management ("KM") community have also used this ranking. Pór (1997), and a number of people – especially in the organizational knowledge management communities have also discussed the transformations of data to knowledge38. here are also some fascinating literary and musical uses of what is initially a commonsense ranking of the words39.

Coombe’s diagram succinctly illustrates how elements of data are aggregated through a series of cognitive transformations into power to influence events. As will become evident in the course of this work, I do not imply here that "cognitive" processes are necessarily limited to human brains. Any sufficiently complex cybernetic system should be able to carry out the kinds of transformations discussed here. In a Popperian sense, each level of aggregation and transformation increases the epistemic quality of the information by increasing the coherency, number and robustness of the connections between the information and the world of reality (i.e., as hypotheses are transformed into tested theory and demonstrate their power to influence external events).

My elaboration on Coombe's framework is based on a Popperian evolutionary epistemology (Popper, 1959, 1963, 1972) as explored in Hall (1983), rather than Polanyi's epistemology (Jha 1999; Mullins ????).

Although Michael Polany's (1952, 1967) concepts of personal and tacit knowledge are used by some in the organizational knowledge management discipline to establish a framework for judging the epistemic quality of information claimed to be knowledge, I personally still follow Popper's concept that personal beliefs must be connected to external reality via some form of testing against that reality before they can be called knowledge. As elaborated in the following text, Coombe's framework provides a useful metaphor for explaining in terms of epistemic quality how aggregation and testing adds value to information to create knowledge and power. Popper would place tacit knowledge in the subjective World 2, while Polanyi's contributions to the meaning of knowledge is discussed in the section on organizational knowledge management.

Below, I have somewhat modified Coombe's expression of the epistemic quality hierarchy to better focus on the cognitive issues I wish to treat in more detail in the remainder of this paper.

The term data is used in a wide variety of contexts. In this paper, I am using data in the sense that it is the atomic level of information, i.e., undifferentiated or disconnected text. Without structure or connections to other information, data or strings of text are essentially meaningless, either in logic or in a knowing subject. In other words, without structure and an application to parse and process the content according to some set of rules, the sequence of bits contained in a binary file is useless.

When value (or meaning) is added to data by collecting, classifying and linking elements together into coherent tables or records, the links and surrounding elements of data provide a context that help humans (in World 2) or computers (in World 3) assign meaning to the data. Relational database applications provide technology to help collect, tabulate and link relatively low level kinds of data elements, and can automate processes to extract information into useful outputs.

Operationally defined, knowledge is appropriate information that is known and available to the user when and where it is needed for a purpose.

Deeper concepts of knowledge and semantics depend crucially on their philosophical and psychological foundations, and consequently are contentious to define. What is considered to be knowledge and how it comes to exist falls within the philosophical domain of epistemology, as well as having objective foundations in biology, ethology and cognitive psychology. As developed in this work, my concept of knowledge is developed in the framework of evolutionary epistemology40 - first named as such by Donald T. Campbell. "... A piece [i.e., element] of knowledge is an object which we can use to produce (generate) predictions or other pieces of knowledge.... True knowledge is an instrument of survival [i.e., 'true' knowledge works when applied in nature]. Knowledge is power. There is no criterion of truth other than the prediction power it gives. Since powers, like multidimensional vectors, are hard to compare, there is no universal and absolute criterion of truth." (My italics - Turchin 1991).

New knowledge is built by assimilating and organising data and information and relating this to experiences with external reality and to prior knowledge. In linguistics, semantics refers to the relatively mechanical processes and rules by which a brain or computer infers meaning from the vocabulary and grammar (syntax) of natural language (whether spoken or written - Akman 1997). In a metaphysical sense, semantics includes the rules and processes by which unevaluated information of any kind is given cognitive meaning (Block in Press). In an evolutionary epistemology, knowledge is built semantically by making inferences and evaluating them against prior knowledge and external observations. Bad inferences don't mesh well with what is already known and observed, and are quickly discarded, successful inferences count as knowledge until shown to be false through conflicts with observed reality. Reflecting back to the prior discussion of Kuhnian revolutions: A new inference may not mesh well with the existing body of knowledge, but if some of the existing items of "knowledge" are scrapped, the new inference may help what remains to gel into a larger and more robust network of semantic or logical connections than what is replaced. As will be elaborated later, this process also relates well to Popper's (1972) evolutionary theory of knowledge.

People learn semantic processes along with language, professions and disciplines. Authors use the shared semantic processes to select, classify, evaluate and organise information into meaningful communications or documents. In this sense, because documents include semantic structure, other people can readily use knowledge recorded by one person (an author). Such semantically assimilated knowledge is substantially more valuable to humans than information in a raw database, which must be assimilated, organised and evaluated each time it is encountered anew.

In a sense, culturally transmitted semantic processes are major parts of disciplinary paradigms.

Intelligence is used here in the military sense41, i.e., intelligence is the cognitive product resulting from actively collecting, processing, integrating, analysing, evaluating and interpreting elements of existing knowledge. This cognitive product is often presented in the form of informed predictions, or in scientific terms, hypotheses about the state or future of external reality. As such, intelligence represents a valuable extrapolation beyond unassociated elements of knowledge. Intelligence grows as more knowledge (i.e., prior connections with reality) is assimilated into the cognitive product.

Coombe says that wisdom represents the "application of intelligence through decisions... Intelligence is of no practical use unless applied by making a decision for action". Merriam–Webster's Collegiate Dictionary42 qualifies "wisdom" against its synonyms as follows:

SENSE, COMMON SENSE, JUDGMENT, WISDOM mean ability to reach intelligent conclusions. SENSE implies a reliable ability to judge and decide with soundness, prudence, and intelligence <a choice showing good sense>. COMMON SENSE suggests an average degree of such ability without sophistication or special knowledge <common sense tells me it's wrong>. JUDGMENT implies sense tempered and refined by experience, training, and maturity <they relied on her judgment for guidance>. WISDOM implies sense and judgment far above average <a leader of rare wisdom>.

Possibly a better term for the idea of wisdom in military affairs (as discussed below) would be "strategy"43.

Following Coombe's structure, in a value hierarchy of terms based on epistemic quality, wisdom or strategy would represent intelligence (i.e., hypothetical prediction), which has been further informed through active testing against the world of reality and thus transformed into theory (again using the scientific meaning of the term).

The term power has many different meanings44. Influence is the application of wisdom to achieve power. In competition, evolution or conflict, power is the ability of an entity (individual or organization) to affect or control unfolding events to its own ends. In the broad sense, this can be defined as "strategic power"45. Power in such circumstances is purely relative. One entity's abilities to control events are measured against another's abilities to see who wins the day.

Strategic power has three major sources developed through the epistemic transformation processes discussed above:

epistemic power - the wisdom to know how to apply power,

will power - the decision or will to apply power,

logistic power - available resources enabling the application of power.

Here, I wish to focus on the importance and sources of epistemic power.

Adaptation is a cybernetic process (Beer 1981) by which an entity (individual or collective) changes or evolves through time in order to achieve a particular goal. Where the cybernetic process is intrinsic to the entity, and its adaptation may involve internal changes to the cybernetic process itself, the entity can be termed a “complex adaptive system”46. Individual organisms, biological species, social organizations (commercial and military) and even whole nation states are complex adaptive systems relevant to this discussion. Typically the goal of such a system or entity is to achieve and maintain enough power to survive in an environment of competition or conflict.

In biological species over evolutionary time, the assumed "goal" of a species is its continued survival in a competitive environment; where adaptation is a product of the species' genetic heritage as it changes from one generation to the next. In other words, to gain epistemic power. Such adaptations represent a form of knowledge about the external environment (Plotkin 1994). Non-humans adapt as individual organisms by learning or physiological change. The human species, in addition to adapting and learning on an individual basis, can also culturally transmit knowledge to other individuals via language and World 3 productions to assist their adaptations. Individual humans can also consciously alter their cognitive processes to better adapt to external change, and in turn can transmit these cognitive adaptations culturally. As will be seen in Episode 4, "Cultural" adaptation also applies to collective human entities that transcend the individual level of organization, such as as businesses, military bodies and nations.

Figure 2: Karl Popper's (1972) three worlds of knowledge. World 2 is an emergent property based in World 1. World 3 is an emergent property based in World 2.

Figure 2 illustrates my understanding of the relationships between Popper's three worlds and how adaptation and evolution through natural selection relate to or determine the nature and contents of these domains. Some of the ideas relating to this picture will be introduced here, but they will be substantially elaborated in Episode 447.

World 1 is physical reality. Our existence as organisms is based World 1 and is enabled and constrained by its physical laws. The phenomenon of life is fuelled and maintained by the metabolic flux of energy through our organic systems working in accordance with the laws of physics, chemistry, thermodynamics and cybernetics (Morowitz 1968).

To survive, organisms must self-regulate and control their internal fluxes of metabolic energy. Physiological adaptation within individual organisms is the result of this kind of self-regulation. If the bounds of self-regulation are exceeded the organism dies. Consciousness is a particularly sophisticated component of the self-regulatory apparatus, and most likely evolved to facilitate control over the physical world to better protect and regulate internal metabolism through the ability to acquire and control external resources. At the individual level, the ultimate control over external resources is represented by strategic power, which is achieved through epistemic power.

Life as we know it also depends on the existence of a system of heredity that:

controls development of the organism - i.e., the physical phenotype of an individual is at least partially determined by the genes it inherits from its parent(s); and

is replicated, mutated (to a tiny degree in any one generation), recombined and passed on by at least some individuals of one generation to form the next generation.

In biological species this heredity is shaped and changed over many generations of time through the processes of natural selection resulting from the differential survival and reproduction of individual phenotypes that are to some degree determined by particular genotypes. In other words, natural selection leads to genetic adaptations at the population and species level by selectively removing those genes and gene combinations which do not work particularly well in the environment occupied by the species. What is left encoded in DNA genomes is tested experience (i.e., knowledge) about what individuals of the species have required in the past in order to survive and reproduce. The encoded knowledge passed down the generations has an existence that transcends the lives of any particular individuals carrying that heredity at a particular point in time. It is this transcendent knowledge about what organisms needed to survive and reproduce in World 1 that formed the original basis for World 3. In Popper's concept:

The three worlds are so related that the first two can interact and that the last two can interact. Thus the second world, the world of subjective or personal [i.e., biological] experiences, interacts with each of the other two worlds. The first world and the third world cannot interact, save through the intervention of the second world, the world of subjective or personal experience.... [T]hat is, with the second world as the mediator between the first and third. (Popper 1972:p 155)

In the figure, the solid arrows show the direct interactions, and dotted arrows, those relationships mediated by actions between worlds 1 and 3 that are formulated in and observed from the second world. World 1 is the physical world and includes all physical structures and processes, worlds 2 and 3 ultimately are also evolved products of World 1. To further explain what the arrows signify:

World 1 is the source from which World 2 is formed. World 1 provides the biochemical substrate, sources and sinks for energy fluxes, and the governing laws that determine (i.e., permit and cause) the formation of self-regulatory cybernetic systems built using World 1 apparatus. That is, the physical structure and fluxes maintaining the body of the biological organism itself and driving the evolutionary processes are also World 1 phenomena (the underlying reasoning behind these assertions will be developed in Episode 4, but see Morowitz 1968). World 2 in the broad sense is the collection of emergent, evolved dynamic organic processs that are fed and housed within World 1 matrices.

World 2 is an emergent property of World 1 comprised of the cybernetic logic responsible for the self regulation and self maintenance of dynamic organic processes. Initially this logic would have consisted of comparatively simple regulatory feedback loops. However, as organic life evolved greater complexity and regulatory capabilities through genetic natural selection, increasingly powerful functions associated with regulation such as memory and consciousness of self emerged - to the extent that humanity now consciously aware of and regulates or controls (or at least impacts through conscious actions) a substantial fraction of the Earth's organic activities.

The processes involved in the reproduction of complex organisms or cognitive entities are themselves quite complex. The fertile seed or egg bears no obvious relationship to the parent organism(s) that produce it. However, the seed or egg contains within its World 1 structure essentially all of the hereditary knowledge required to control, regulate, develop and grow another self-regulating and self-maintaining adult organism. Even during the lifetime of one organism, the atoms comprising the DNA molecules encoding the heredity are progressively diluted and replaced many times over as the cells carrying the heredity multiply from a single celled zygote to produce the adult organism, yet the hereditary knowledge remains intact as it is replicated thousands of times across many billions of cells forming the adult organism; and furthermore, the heredity is passed on essentially intact (according to the genetic rules of mutation, recombination and assortment) to zygotes that will selectively48 survive to form subsequent generations. The hereditary knowledge is real, yet completely intangible in that it can exist independently of the molecular substrate that normally encodes it. Hereditary knowledge is capable of being expressed in a variety of physical forms, e.g., sequences of nucleotides in DNA or RNA, amino acids in proteins, or even sequences of letters in a printed publication or electrons transmitted over a wire (e.g., see the human genome project). With appropriate tools it is even possible to turn the coded sequences of electrons back into meaningful DNA (e.g., see Genomes to Life). What was initially probably only a regulatory loop that helped pieces of a protoorganism maintain their self productive and self maintenance capabilities when the parent body was fragmented by external forces, has become a world of persistent knowledge that can exist independently of the structures that encode it. World 1 consists of atoms, molecules and the fabric of space, World 2 consists of self-regulating and self-maintaining dynamic processes in World 1, while World 3 consists of real, persistent but totally intangible knowledge self-maintaining organisms require in order to maintain their dynamic structure. World 2 organisms require access to this accumulated World 3 knowledge in order to maintain their existences in World 1.

Popper's awesome genius was to recognize that other forms of persistent knowledge (i.e., experience, theories, etc. expressed in language on paper or in other forms) were akin to biological heredity in that they also had an existent and potential adaptive value in World 1 entirely independently of the knowing subjects or the physical objects encoding the knowledge. In the same way that genetic heredity is reproduced as World 3 knowledge; World 2 experience, theories and logical understandings can be produced linguistically or in other ways as persistent World 3 artifacts (i.e., as represented in books, computer programs, training films, etc.) that have an existence independently from any physical World 1 individual or the World 2 cognitive processes of that individual. An essential point not specifically made by Popper is that World 3 artifacts can be replicated, transcribed and transmitted into and across a variety of different media independently from any perception of the knowledge in World 2 cognition. Also, in the same way that persistent knowledge from World 3 determines the dynamic developmental and regulatory processes in World 2 that in turn enables the existence of a biological entity in World 1, the World 2 consciousness of an individual can recall persistent knowledge from World 3 to guide its World 1 processes and activities.

As defined by Popper, World 3 is virtual in that artifacts of knowledge can persist in World 3 independently from any specific physical representation in World 1. However, there are inferred logical connections between World 3 artifacts and physical objects and processes in World 1. For example, most of the elements of genetic knowledge carried in the genomes of living species at any point in time have been selected to work together harmoniously to form World 1 phenotypes based on knowledge that has worked successfully in the past. Thus, genetic knowledge has a clear (stochastic) causal derivation from World 1, and the inferred logic represented by the extant genetic knowledge that has survived selection describes developmental processes that past experience predicts will again work successfully in the future.

Popper argued that the World 3 artifacts produced by conscious individuals to describe World 1 phenomena via their World 2 processes thus have an inferred connection to World 1 because they can describe and make logical predictions about World 1 phenomena. This knowledge may be true, false or incomplete. It is often only tentative. As is the case for genetic information, World 3 artifacts created by humans can represent knowledge about World 1 that exists independently from any knowing individual. However, knowledge can be recalled from World 3 into World 2 cognitive systems for conscious use or testing; where the logic of the knowledge can be evaluated and further filtered by predicting and observing World 1 phenomena to determine whether the knowledge artifact is pragmatically useful. World 2 consciousness can selectively remove artifacts that are false and useless from World 3 in much the same way that natural selection works on genetically transmitted knowledge, such that World 3 knowledge may be used to facilitate individual, cultural and species adaptation. Thus all of the inferred connections between World 3 and World 1 can only be tested and observed via actions mediated by World 2 cognitive processes.

The next section continues developing ideas gleaned from the pragmatic world of military affairs, to present a generic adaptive process to show how any complex cybernetic system or "entity" can transform data into epistemic power.

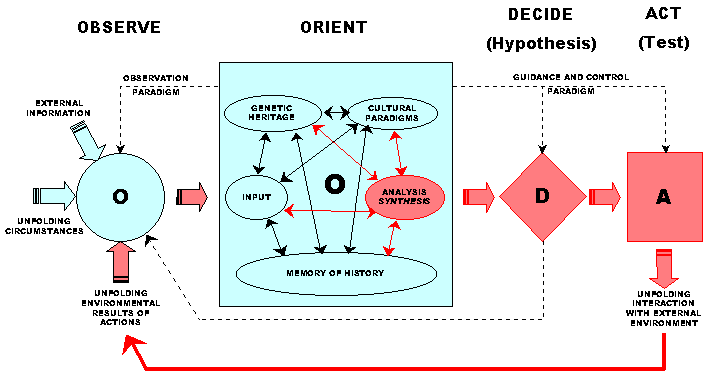

Col. John Boyd was an Ace fighter pilot in the Korean War and became one of the 20th Century's greatest strategic thinkers (Hammond ????; Coram 2000). Boyd's thoughts on the subject of developing winning military strategies (i.e., strategic power) have strongly influenced the defense community's development of doctrines49. Without using this term, Boyd focused on how to achieve epistemic power. Boyd's conception of the cybernetic process of adaptation is summarized under the term "OODA loop"50, where OODA is the acronym for an iterative feedback loop involving Observation, Orientation, Decision, and Action. One cycle produces an action. Iteration and associated feedback from experience, which changes the information content of the orientation process (i.e., learning) result in adaptation. An entity achieves power over an enemy by adapting faster and more effectively to control events to its benefit and the opponents' detriments (i.e., the entity “acts inside the opponent’s OODA loop”). I discuss Boyd's concept and further thinking on the subject in some depth, as this brings together several threads in my argument. Figure 2 summarizes Boyd's concept of the flow and processing of information in an adaptive response.

Figure 3. Based on Fadok's (1994) and War, Chaos and Business's depictions of John Boyd's OODA Loop

The OODA Loop is comprised of the following major elements that would apply to any entity seeking to achieve epistemic power in a competitive environment. For example, the cybernetics of a biological species' adaptation by natural selection is also mapped by the OODA loop51, as will be discussed in Episode 4. The discussion here focuses on adaptation by individual entities with cognitive and learning capabilities. Such entities can be individual people or organizations, as will also be elaborated in Episode 4.

Observation covers all aspects of collecting data and assembling information on the current state of the entity's external environment. This includes observing the effects of entity's own prior actions on external circumstances in the unfolding reality, effects of competitor's actions and other changes, as well as taking cognizance of other external sources of information. Quality and quantity of input information contributes significantly to determining the effectiveness of the actions. To achieve epistemic power the entity should both work to improve the quality and quantity of its own inputs, and act where possible to confuse or disrupt its competitors' inputs – thus diminishing the opponents' powers.

In Boyd's OODA schema (Boyd 1976), "orientation" covers the adaptive semantic/cybernetic processes of building and maintaining knowledge (what Popper calls 'knowledge growth') about the continuously changing world. According to Spinney (1997), a close associate of Boyd's, orientation is the adaptive process by which an entity continually breaks down, evolves and shapes its interior mental paradigms (used in the Kuhnian sense), to better enable the entity to respond to and shape external conditions. First, this is process of taking observations from World 1, combining them with knowledge from World 3 and individual memory to build and criticize models or representations of reality in World 2, and perhaps producing further knowledge artifacts in World 3. The criticism that shapes the knowledge is carried out by cognitive processes in World 2. Popper describes the process of knowledge growth through criticism or conjecture and refutation as follows:

...[T]he growth of our knowledge is the result of a process closely resembling what Darwin called 'natural selection'; that is, the natural selection of hypotheses; our knowledge consists, at every moment, of those hypotheses which have shown their (comparative) fitness by surviving so far in their struggle for existence; a competitive struggle which eliminates those hypotheses which are unfit.

This interpretation may be applied to animal knowledge, pre-scientific knowledge, and to scientific knowledge. What is peculiar to scientific knowledge is this: that the struggle for existence is made harder by the conscious and systematic criticism of our theories. Thus, while animal knowledge and pre-scientific knowledge grow mainly through the elimination of those [individuals] holding the unfit hypotheses, scientific criticism often makes our theories perish in our stead, eliminating our mistaken beliefs.

This statement of the situation is meant to describe how knowledge really grows. It is not meant metaphorically, though of course it makes use of metaphors.

Boyd argues that this adaptive process of knowledge growth is best achieved by an iterated sub–processes within the orientation stage. First, destructively disassemble existing paradigms into their component elements of information and syntactical connections. This effectively destroys preconceptions. Second, 'inductively' reassemble the components to create new and more coherent paradigms. Third, determine by deductive testing how well the newly created paradigms match current observations and prior knowledge of the world. Iterate the destruction/creation process until the paradigms "demonstrate internal consistency and match–up with reality". Boyd noted this orientation process is enabled, shaped and informed by the entity's prior experience and its genetic and cultural heritage (i.e., World 3 knowledge). As such, the destruction/creation process itself can be altered through feedback into World 3 via individual and culturally transmitted experience (i.e., training) to better adapt it to changing requirements.

In Coombe's terms, orientation represents the processes by which entities achieve knowledge and intelligence. Boyd’s development of these ideas was apparently informed by Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions and Popper's earlier works, but he appeared to be unaware of Popper's later work as published in Objective Knowledge52. However, Boyd's concept, focused on the real world requirements to win battles, is close if not identical to Popper's evolutionary theory of knowledge growth as extended by the evolutionary epistemologists.

Heuer's (1999) book, Psychology of Intelligence Analysis, considers in great depth the mental processes that should be involved in this destruction/creation cycle in the framework of defense intelligence analysis. Although Popper and Boyd are not cited directly, and Kuhn only once, the recommended methodology for developing intelligence estimates is very much that described above:

Scientific method is based on the principle of rejecting hypotheses, while tentatively accepting only those hypotheses that cannot be refuted. Intuitive analysis, by comparison, generally concentrates on confirming a hypothesis and commonly accords more weight to evidence supporting a hypothesis than to evidence that weakens it. Ideally, the reverse would be true. While analysts usually cannot apply the statistical procedures of scientific methodology to test their hypotheses, they can and should adopt the conceptual strategy of seeking to refute rather than confirm hypotheses. ...

Apart from the psychological pitfalls involved in seeking confirmatory evidence, an important logical point also needs to be considered. The logical reasoning underlying the scientific method of rejecting hypotheses is that "...no confirming instance of a law is a verifying instance, but that any disconfirming instance is a falsifying instance." [Wason 1960] In other words, a hypothesis can never be proved by the enumeration of even a large body of evidence consistent with that hypothesis, because the same body of evidence may also be consistent with other hypotheses. A hypothesis may be disproved, however, by citing a single item of evidence that is incompatible with it. ...

.... The intelligence analyst commonly deals with problems in which the evidence has only a probabilistic relationship to the hypotheses being considered. Thus it is seldom possible to eliminate any hypothesis entirely, because the most one can say is that a given hypothesis is unlikely given the nature of the evidence, not that it is impossible.

This weakens the conclusions that can be drawn from a strategy aimed at eliminating hypotheses, but it does not in any way justify a strategy aimed at confirming them.

Circumstances and insufficient data often preclude the application of rigorous scientific procedures in intelligence analysis--including, in particular, statistical methods for testing hypotheses. There is, however, certainly no reason why the basic conceptual strategy of looking for contrary evidence cannot be employed. An optimal analytical strategy requires that analysts search for information to disconfirm their favorite theories, not employ a satisficing strategy that permits acceptance of the first hypothesis that seems consistent with the evidence. (Heuer 1999 - http://www.cia.gov/csi/books/19104/art7.html#rft46) ...

Heuer outlines the recommended analytical process (i.e., Boyd's "orientiation") to build "intelligence":

Step-by-Step Outline of Analysis of Competing Hypotheses

1. Identify the possible hypotheses to be considered. Use a group of analysts with different perspectives to brainstorm the possibilities.

2. Make a list of significant evidence and arguments for and against each hypothesis.

3. Prepare a matrix with hypotheses across the top and evidence down the side. Analyze the "diagnosticity" of the evidence and arguments--that is, identify which items are most helpful in judging the relative likelihood of the hypotheses.

4. Refine the matrix. Reconsider the hypotheses and delete evidence and arguments that have no diagnostic value.

5. Draw tentative conclusions about the relative likelihood of each hypothesis. Proceed by trying to disprove the hypotheses rather than prove them.

6. Analyze how sensitive your conclusion is to a few critical items of evidence. Consider the consequences for your analysis if that evidence were wrong, misleading, or subject to a different interpretation.

7. Report conclusions. Discuss the relative likelihood of all the hypotheses, not just the most likely one.

8. Identify milestones for future observation that may indicate events are taking a different course than expected. ... (Heuer 1999 - http://http://www.cia.gov/csi/books/19104/art11.html)

The process of deciding to take an action is basically one of selecting a hypothesis created within the constraints of the current best–fit paradigm: i.e., if I do A then B is the expected result.

Act on the best–fit hypothesis. Observing the results of the action tests the epistemic value of the decision hypothesis, and these observations should immediately be fed back into the orientation process for the next cycle to help refine or destroy the current paradigms. This is also stressed by Heuer (1999):

Analytical conclusions should always be regarded as tentative. The situation may change, or it may remain unchanged while you receive new information that alters your appraisal. It is always helpful to specify in advance things one should look for or be alert to [what], if observed, would suggest a significant change in the probabilities. This is useful for intelligence consumers who are following the situation on a continuing basis. Specifying in advance what would cause you to change your mind will also make it more difficult for you to rationalize such developments, if they occur, as not really requiring any modification of your judgment. (Heuer 1999 - http://http://www.cia.gov/csi/books/19104/art11.html)

In conflicts and competitions involving humans; knowledge, culture and experience further inform the destructive/creative orientation process. As a fighter pilot in the Korean War, Boyd observed that the only slightly more responsive F86 fighter could achieve an 11/1 kill ratio against the technically better and faster MIG–15. Boyd spent many years of study trying to understand how this could be. He eventually developed the OODA cycle concept and concluded that those entities (i.e., fighter pilots) with the shortest cycle times would have the better and more accurate understanding or knowledge of external circumstances. Because of this they could act first to alter the unfolding environment to their own advantage and disadvantage to their opponents:

Colonel Boyd stated that the ultimate objective of using a superior tempo driven system was to break down the enemy. To do this one must "exploit operations and weapons that: generate a rapidly changing environment … and inhibit an adversary's capacity to adapt to such an environment." Utilizing those actions paralyzes the adversary's mechanism for dealing with his foe's increased tempo. The goal of the process can be easily stated: "simultaneously compress own time and stretch–out adversary time to generate a favorable mismatch in time/ability to shape and adapt to change." (Cowan 2000)

Extended into the broader realm of overall military strategy, the best strategy for an entity to achieve power would often be to attack and confuse the opponents' observation and orientation activities53.

Boyd's work leads naturally into my last major excursion into the military arena – to combine threads on cognitive revolutions and information value. Strategic policies and doctrines around the world are currently in a major state of flux as strategists attempt to incorporate the fruits of the Microelectronics and Knowledge Management Revolutions, together with Boyd's insights about the cybernetics of complex adaptive systems as represented by competing fighter pilots, organizations and states. Staff colleges around the world call this the "Revolution in Military Affairs"54, or more commonly "RMA". Metz and Kievit (1995) provide excellent background on the concept of a military revolution:

...As could be expected with a dramatically new idea, analysts of the RMA have not fully agreed on its meaning. Futurists Alvin and Heidi Toffler, for instance, use a restrictive definition based on macro–level economic structure. They write:

A military revolution, in the fullest sense, occurs only when a new civilization arises to challenge the old, when an entire society transforms itself, forcing its armed services to change at every level simultaneously–from technology and culture to organization, strategy, tactics, training, doctrine, and logistics. When this happens, the relationship of the military to the economy and society is transformed and the military balance of power on earth is shattered.55

From this grand perspective, there have been only two true military revolutions, the first associated with the rise of organized, agricultural society, and the second with the industrial revolution....

Most analysts addressing the RMA, though, have adopted less inclusive and restrictive definitions stressing a “discontinuous increase in military capability and effectiveness.”56

According to Andrew Krepinevich, a military revolution:

...occurs when the application of new technologies into a significant number of military systems combines with innovative operational concepts and organizational adaptation in a way that fundamentally alters the character and conduct of conflict. It does so by producing a dramatic increase–often an order of magnitude or greater–in the combat potential and military effectiveness of armed forces.57

Analysts have concluded that a revolution in military affairs dramatically increases combat effectiveness by four types of simultaneous and mutually supportive change: technological change; systems development; operational innovation; and, organizational adaptation.58

Personally, I believe the current RMA is clearly going to be of Toflerian proportions rather than the kind envisaged by Krepinevich. However, I fully agree with Krepinevich's list of drivers for change. All of these are aspects of the Microelectronics Revolution in technology and the associated cognitive revolution in managing information and assembling knowledge. As the OODA concept discussed above demonstrates, information and knowledge, combined with speed of response, are absolutely critical factors in the cybernetics of power.

The following quote from Metz (2000) expresses the concept:

One of the most important determinants of success for 21st century militaries will be the extent to which they are faster than their opponents. Tactical and operational speed comes from information technology–the “digitized” force–and appropriate doctrine and training [what I have termed epistemic power]. Strategic speed [i.e., logistic power] will be equally important as a determinant of success in future armed conflict. For nations that undertake long–range power projection, strategic speed includes mobility into and within a theater of military operations. Strategic speed also entails faster decision making.

Speed also has an even broader, “meta–strategic” meaning. The militaries which meet with the greatest success in future armed conflict will be those which can undertake rapid organizational and conceptual adaptation. Successful state militaries must institutionalize procedures for what might be called “strategic entrepreneurship”–the ability to rapidly identify and understand significant changes in the strategic environment and form appropriate organizations and concepts. [My emphasis]

The "'digitised' force", faster decision making, and "organizational and conceptual adaptation" are all cognitive processes in the cybernetics of developing epistemic power (Metz and Kievit 1995).

In sum, entities whose OODA decision cycles generate informed actions in less time than their adversaries can increase their strategic and competitive power at the expense of those whose cycles take longer. In an instant of evolutionary time (i.e., in less than a generation), the development of cognitive technologies based on the incredibly shrinking transistor as expressed in Moore's Law have the power to profoundly affect all aspects of organizational decision–making cycles. Cognitive processes that until now were exclusively limited to human brains are being externalized. People, organizations and nation states that do not take cognizance of the impact of new technologies on the decision–making cycle will be overwhelmed by those who do.